After learning the basics of knitting (knit, purl, casting on, and binding off, which I cover in my free How to Knit course), learning how to shape fabric is the next step to unlocking knitting mastery. Fortunately, the techniques for how to increase and decrease are relatively easy to learn. What’s trickier is knowing which one to use in which context.

In my last post, I covered how Mastering Knitted Increases: M1, KFB, and YO. In this post, we’ll discuss the counterparts of increases—knitted decreases—and when and where to use each one.

Onward!

Directional Decreases: k2tog, ssk, p2tog, and ssp

The two most common knitted decreases are the knit two together (abbreviated k2tog) and slip-slip-knit (abbreviated ssk) (and their purl-side counterparts). Both of these decreases turn two columns of stitches into one by working through two stitches at once. Which decrease you choose is determined by which of the two columns you want to remain unbroken, and which you want to disappear.

The directional slant inherent in these decreases can be used to good effect to make some very interesting surface textures (often paired with increases to manage stitch count). They can also be used on their own or in pairs to shape fabric around body parts for good fit.

What Directional Decreases are Used For:

To create symmetrical paired decreases in sock toes, mitten fingers, or shoulder shaping. When the pairs occur very close together (within a few stitches), this is called raglan shaping.

To shape hat crowns. (If only one type of decrease is used the effect will be a slight bias or swirl in the fabric.)

To balance out the extra stitches created by yarn overs in lace fabric.

To create fabrics that have a bias (paired with increases) or other surface textures without changing the shape of the fabric.

How to Make It:

k2tog (knit two together): Knit two stitches together as one. This results in the column on the trailing side* of your work (left column for righties, right column for lefties) remaining unchanged and the column on the leading side merging into it.

ssk (slip-slip-knit): Slip two stitches one at a time as if to knit (which changes the direction they’re lying on the needle so the trailing leg is in front), insert non-working needle tip through both stitches from trailing side, k2tog. This places the stitch from the leading side* column on top, so that column remains unbroken while the other one disappears.

p2tog (purl two together): Purl two stitches together as one. Places trailing-side column on top.

ssp (slip-slip-purl): Slip two stitches one at a time as if to knit, insert non-working needle tip through both stitches from trailing side, p2tog. Places leading-side column on top.

*I write my patterns with hand ambiguity. Please refer to my Glossary and Terms page for definitions of these terms, if necessary.

Centred Decreases: CCD and DCD

What if you don’t want your fabric to slant in a single direction when you decrease, but you want something more centred?

One option is to use raglan decreases, as discussed above. But sometimes, decreasing three stitches into one is the preferred option. In that case, you’ll want to use a centred decrease, which brings the two columns on either side of it into the centre. Again, whether the side stitches lay on top or behind the centre column will create two entirely different looks.

Centre column on top: Central Chain Decrease (abbreviated CCD).

Centre column on the bottom: Double Central Decrease (abbreviated DCD).

What Centred Decreases are Used For:

- Creating hat crowns that don’t shift as they decrease, but ascend straight up to the top.

- In the 3-in-1 or 5-in-1 Pickup technique for creating gapless thumbs.

- Anywhere you want to decrease two stitches at once while creating an intriguing effect between them.

How to Make It:

CCD (central chain decrease): Slip two stitches together as if to knit, slip next stitch as if to knit, insert non-working needle into all three stitches from trailing side and knit together. This creates a prominent centre column, with the other two disappearing behind it.

DCD (double central decrease): Slip stitch as if to knit, k2tog, use non-working needle to pass the first slipped stitch back over the stitch just worked. This creates a less noticeable texture, with the side columns creating a little upside-down chevron over the centre column.

Binding Off (BO)

Unless you’re still working on your very first swatch or project, you likely already know at least the Basic Bind Off. Of course, there are many other bind offs you can use to finish your work, but when it comes to decreasing stitches for fabric shaping, the Basic Bind Off is the most common.

What Bind Off Decreases are Used For:

Finishing a fabric piece so the stitches don’t unravel.

Creating shaping at the shoulder, underarm, or anywhere else you need a few stitches finished perpendicular to the fabric columns for structure or shape purposes.

How to Make It:

Work two stitches in pattern. Using non-working needle, insert tip into first stitch worked and pass it over the second stitch worked and over the end of the needle. (One stitch bound off.) Work another stitch, then bind one off in a similar manner for as many stitches as you need to bind off.

For a photo and video tutorial, refer to Basic Bind Off. You can also check out my other bind off tutorials for various types of fabric.

Keeping Track

Like increases, decreases often occur at regular intervals across rows or columns.

One way to keep track of where you need to increase or decrease is to put a stitch marker right before or after the required stitch (depending on which way it leans).

To keep track of rows between decreases, you could use a row counter or make tally marks on your pattern or another paper.

However, it can be helpful to be able to recognize what your decreases look like at a glance, and what counts as the “last row decreased.” For help with this, check out Recognizing Increases and Decreases.

And be sure to check out my shop to pick up any of the patterns mentioned in this post that you find interesting.

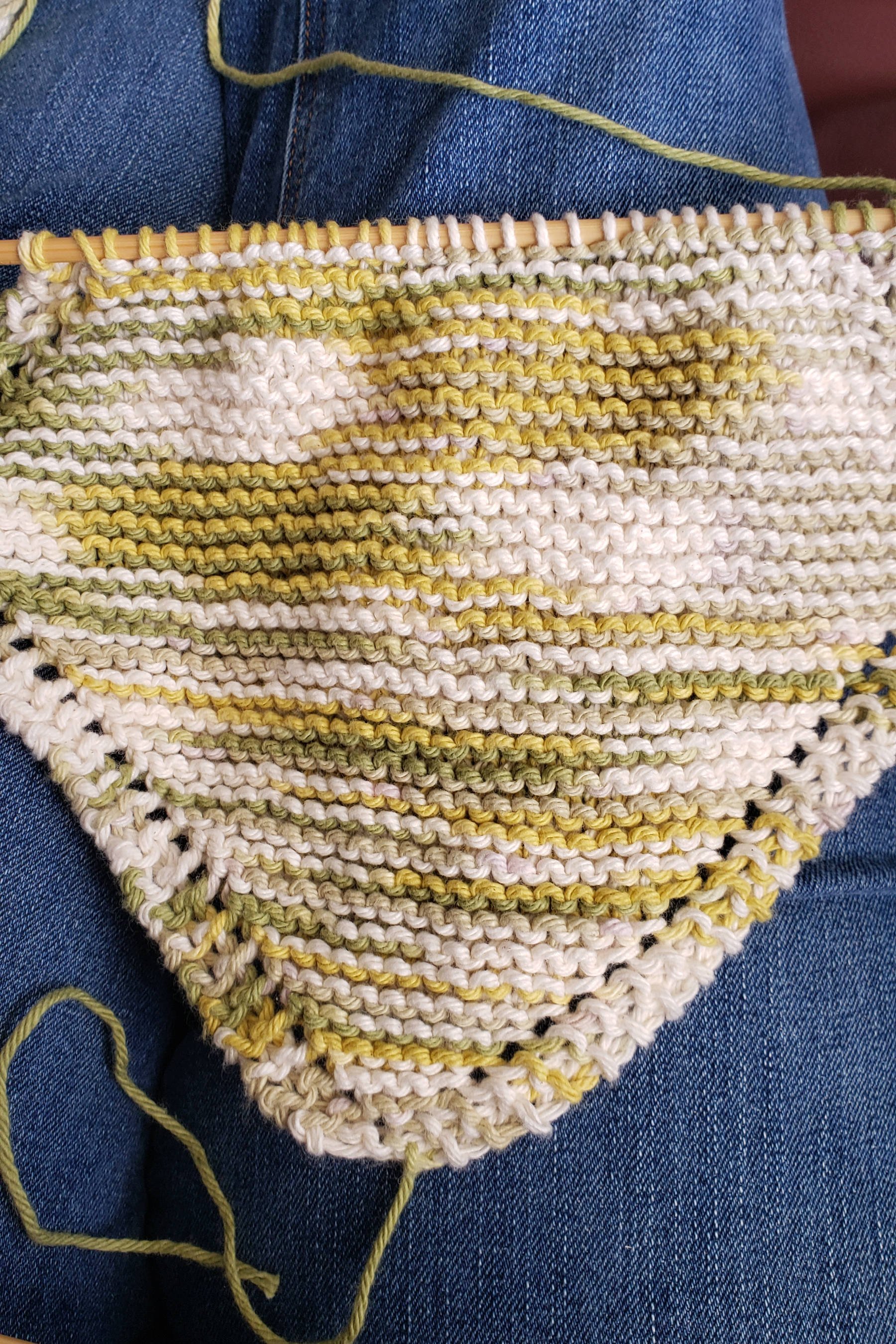

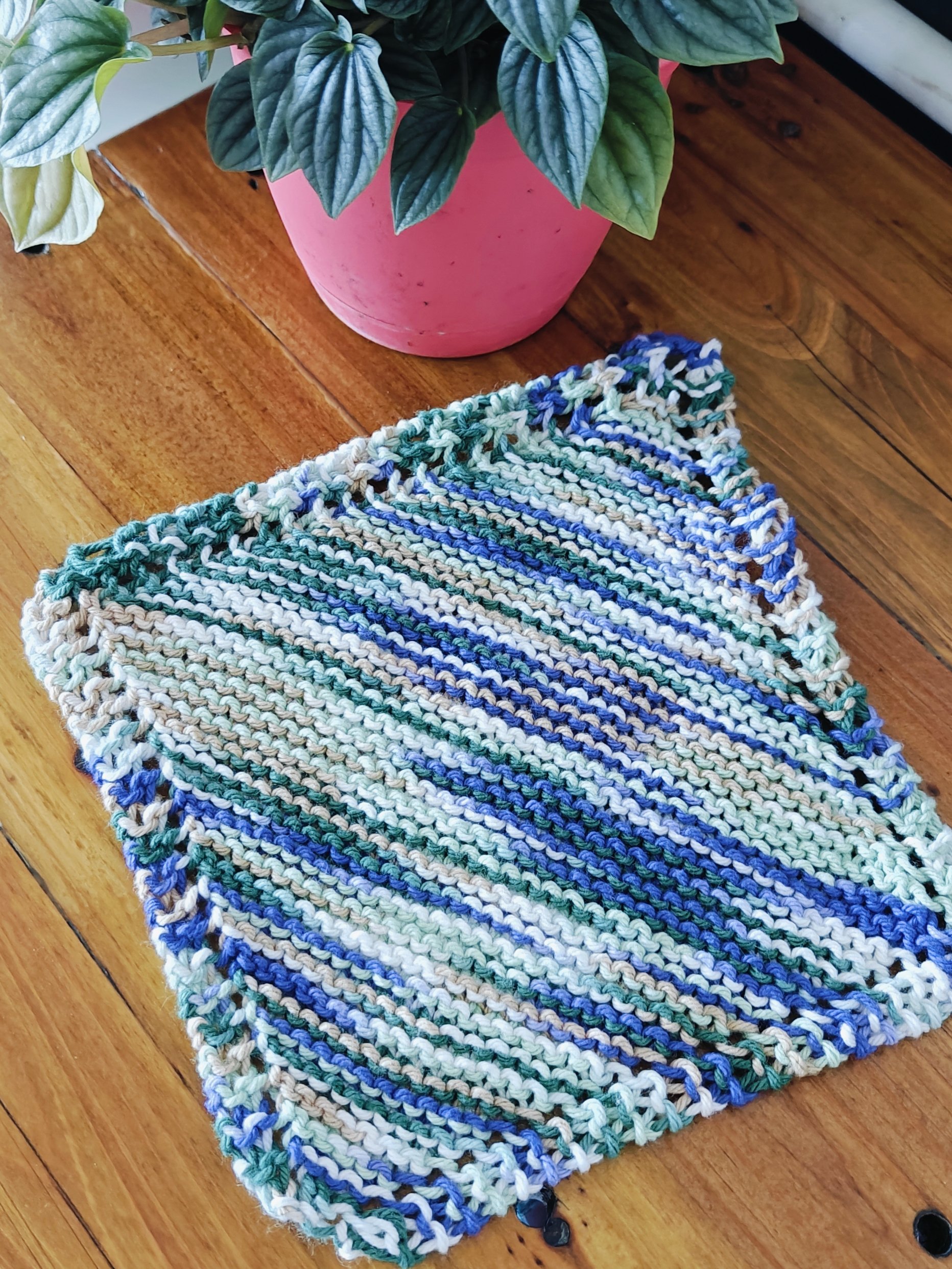

Knit Dishcloth Pattern

To practice some basic increases and decreases so you can start to see how they change the fabric, I recommend practicing with a knit dishcloth. This common pattern is knit on the bias (from corner to corner).

Basic Knit Dishcloth

You’ll need:

5 mm (or US 8 or UK 6) straight needles

1 50-gram (or 1.76-ounce) ball worsted-weight kitchen cotton yarn (such as Bernat Handicrafter Cotton or Knit Picks Dishie).

Yarn needle

Method:

Cast on 5 stitches.

Increases:

Knit 2, yarn over, knit to end. Repeat until you have 44 (48, 52) stitches.

Decreases:

Knit 1, k2tog, yarn over, k2tog, knit to end. Repeat until you have only five stitches. Bind off. Weave in ends.

To make the cloth into a square shape, wet block.

Happy knitting!